PROGRAMMING FOR HIGHER EDUCATION

Is space the final frontier?

Perhaps. But unlike the seemingly endless expanse of the universe, physical or built space on college campuses is a limited resource. When optimized, it has the potential to be a strategic asset. Well programmed campuses can be a powerful tool to support the mission and goals of the institution rather than merely warehouse faculty, staff, and classrooms.

Higher education institutions are confronted with many challenges: adapting to changing pedagogies, financial pressures and meeting the expectations of faculty and students. In response they must ensure that physical campuses provide an effective learning environment for students, are efficient and financially responsible with budgets, and support efforts to attract and retain the best faculty.

In the earliest days, university campuses provided students a place to learn (classroom or lecture hall), a place to study (library), and a place to eat and sleep (dormitories). Professors could expect an office for student meetings, preparation, and research. The modern campus has undoubtedly evolved beyond those basics and will continue to do so, but how?

In an era of unprecedented change and advancing education technology (MOOCs*, virtual reality, online curriculum); what is the role of the college campus and its assortment of spaces? Fundamentally the campus enables individuals to come together to research, educate, learn, and work in ways that are less effective if done remotely or in isolation. The campus, therefore, acts as a magnet, attracting a breadth of disciplines, skills, and generations to create a community of academics and learners. Campuses connect people.

From a campus master plan to a building, down to the rooms within, the design can enable or hinder interaction –formal or serendipitous– and interaction over time is what creates connection.

*Massive Open Online Classes

STUDENT SUCCESS

Connection is identified as a critical component to student success; a primary concern of academic institutions as scrutiny is placed on outcomes to justify the value of ever-increasing tuitions. Student success is not simply earning a diploma. It is also measured by employability and earnings, and is evaluated to provide some justification for the investment in a degree. An internet search “measuring the value of education” yields a plethora of responses.

So, what does connection mean for a college student, and how does it support successful outcomes? Students who

1) connect with their peers,

2) connect with their professors, and who can

3) connect their knowledge to the workplace

are more successful than those who don’t. Campus spaces must change to better support these connections, both inside the classroom and out.

Connection to Peers

“When a student connects to campus and develops a social life they will do better academically,” says Kevin Druger, president of NASPA: Student affairs administrators in Higher Education.

The campus experience must deliver more than corridors to connect destination points, dorm rooms, dining halls, and quiet study carrels. Opportunities for connection should be provided via “touch down” spaces conveniently located throughout the campus that enable spontaneous, ad-hoc gathering to discuss new ideas, solve problems, or even plan for the weekend.

By centralizing services and support spaces, “hubs” are an effective place to facilitate meaningful interactions not only between students but also with faculty and staff. Exploring opportunities to make facilities multi-disciplinary, supporting students and faculty from various departments, we can begin to break down silos, encourage breadth in thinking and context, and foster innovation in pedagogy and practice.

Connecting Theory to Practice

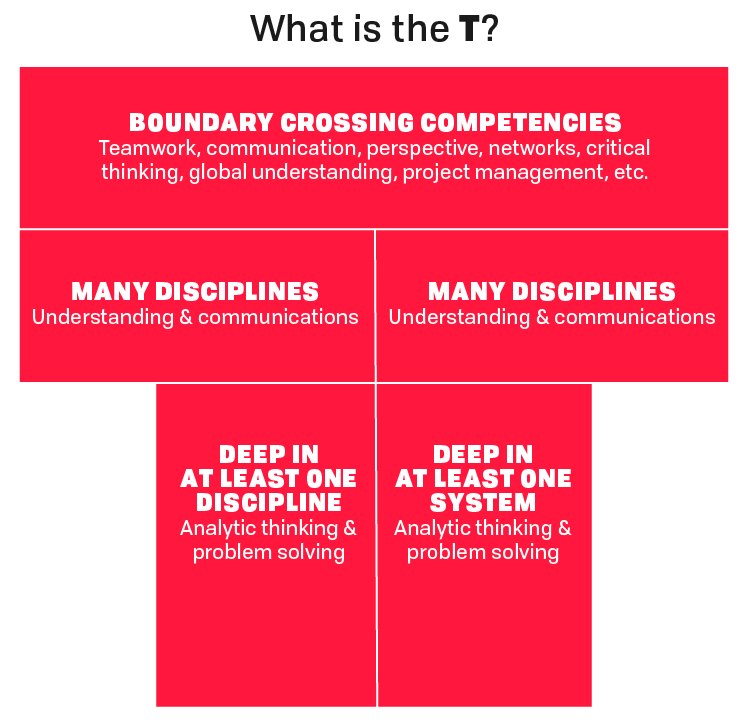

Educators recognize the need to connect a student’s academic efforts to their post-graduate life. Currently, only 36% of professionals feel that colleges and universities are preparing students for the outside world. It is no longer enough to excel in a single field of study. Employers and educators are increasingly placing importance on boundary-crossing competencies such as teamwork, communication, perspective, networks, and critical thinking across many disciplines.

Today’s fast-paced business environment demands immediate productivity from every hire. Educational institutions are being asked to fill in the gap by graduating students with “instantly productive” skills and abilities.

When meeting with incoming families, Susan Bolton, President of the College of Wooster, discusses the importance of connecting beyond the classroom, even to the surrounding community. “When each of the liberal arts colleges of Ohio were established, (Denison, Kenyon, Oberlin, Ohio Wesleyan and the College of Wooster) the prevailing philosophy was to sequester students, allowing them to focus on their individual studies, removing distraction.

The result is rural campuses, separated geographically from towns and communities, and the opportunities to engage students in the practical application of their knowledge. Knowing that these types of connections deepen their learning and better prepare them, we work to overcome this obstacle to provide these opportunities.”

“The people we like to work with are T-shaped. We want people who can wrap their head around the whole thing and be part of teams,” said Jim Spohrer, who heads up university partnerships for IBM.

David Guest first referenced the concept of the T-shaped Employee in 1991, extending beyond the single subject expert. The horizontal stroke of T-shaped people is the ability to work across a variety of complex subject areas with ease and confidence.

Working as Teams

Interdisciplinary competencies. Demonstrated preparation for the workplace. The traditional double-loaded corridor of department classrooms or offices is not the model for space to deliver these objectives. The Active Classroom Model is a step in the right direction. In addition to this, functionally designed spaces must be provided to support teamwork outside the classroom, as well as spaces for focus work and creating. Departmental silos should be penetrated to support the development of integrated curricula, as well as cross-pollination and the sharing of ideas– much like the operations of highly-effective organizations. Put simply, Integrated curricula calls for integrated spaces that share resources, increase utilization and operational efficiency.

One barrier to students utilizing office hours may be the office itself.

The debate over office versus open space continues to rage in the business world.

THE ACADEMIC WORKPLACE

Extensive research has been done to investigate how to improve facilities for students, yet far less has been done to improve the campus as a workplace for its faculty. In fact, the academic workplace is generally not optimized and is typically built on outdated planning principles.

In current discussions about allocations of space on campuses, the faculty office is frequently under attack. Offices in the commercial sector are eliminated in favor of open space. Should we do this in academia as well? The ability to connect to students and peers is a good thing. So, eliminating office walls would be too, right?

The debate over office versus open space continues to rage in the business world. The beneficial impact of open space on collaboration and team effectiveness is well documented; as is the negative impact on personal productivity and the ability to focus. In fact, open space is rarely successful when applied unilaterally, but it can have a positive effect when used as one element in a kit of parts; an assortment of spaces and environments designed to support an organization’s unique multi-faceted needs.

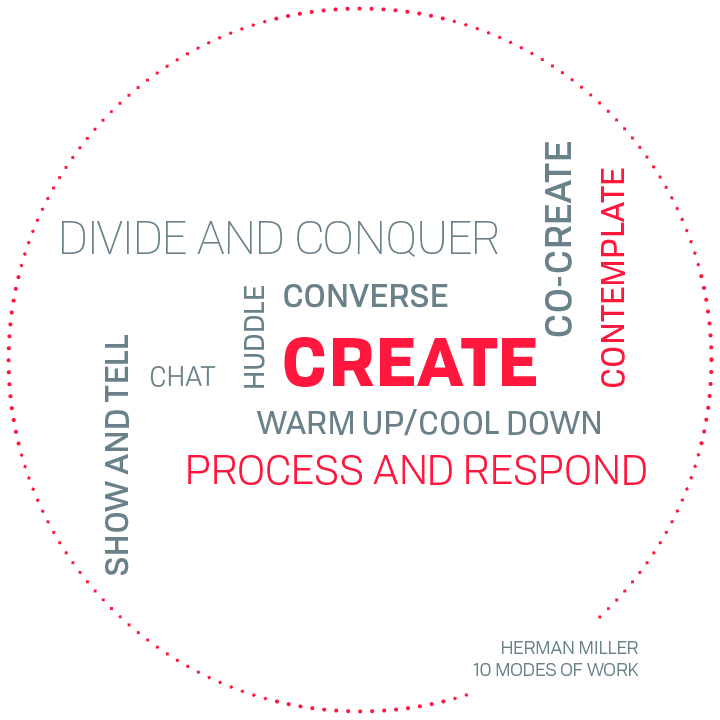

Workplace strategists understand that we work in a variety of ways, and though the office may have a role, it may not be best suited to support them all. In fact, Herman Miller’s research has identified ten distinct work modes. What happens during a workday is far more nuanced than the binary labels or “focus” or “collaborate.” A well-designed workplace thoughtfully addresses this variety of daily functions.

Research into the “day in the life” of faculty identified that their work is multi-modal, lacks universal patterns, and that faculty use spaces all over the campus. They are typically entirely autonomous and mobile; they are resilient and resourceful and able to adapt to less than adequate spaces. (The Secret Life of Faculty, Brian Reid 6/23/2015). Perhaps professors cling vehemently to their offices, despite the idea that it may not meet their workplace needs, is that they are symbolic. The office may represent permanence or tenure, convey their personality, or display accomplishments. It demonstrates they are there and they matter.

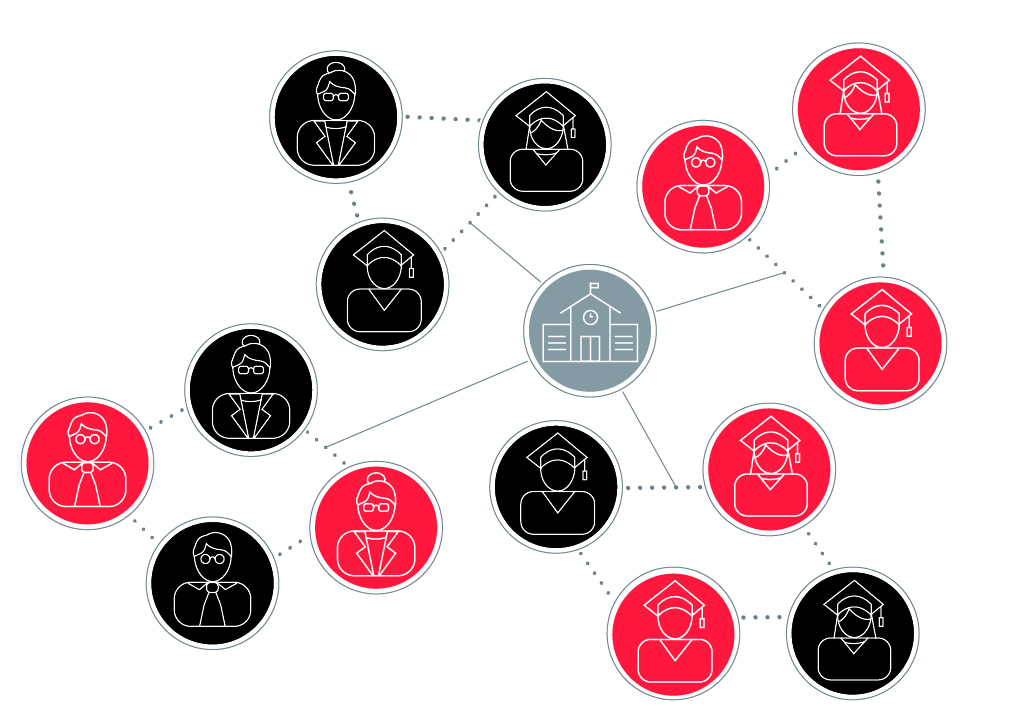

The quality of the workplace is a critical component in attracting and retaining talent, no less so in academia. Carnegie Mellon lists Recruiting and Retaining World Class Faculty as a top priority in their 2025 Strategic Plan. To do so, they recognize the need to seek out individual excellence, but to then create a network that promotes engagement among faculty, interdisciplinary connections, connections with administrators, and connection to junior faculty through mentorship.

Creating a workplace that supports these kinds of connections requires the provision of resources beyond the office. It requires a campus that provides spaces to facilitate and encourage working together.

CAMPUS FACILITIES AND OPERATIONS

The suggested evolution of campus spaces includes larger classroom footprints to support active learning models, in-between spaces for ad-hoc connecting before and after class, immediate and functionally designed break out support for faculty and student collaboration, and “maker” spaces and venues for applied learning. How can campuses accommodate this additional space?

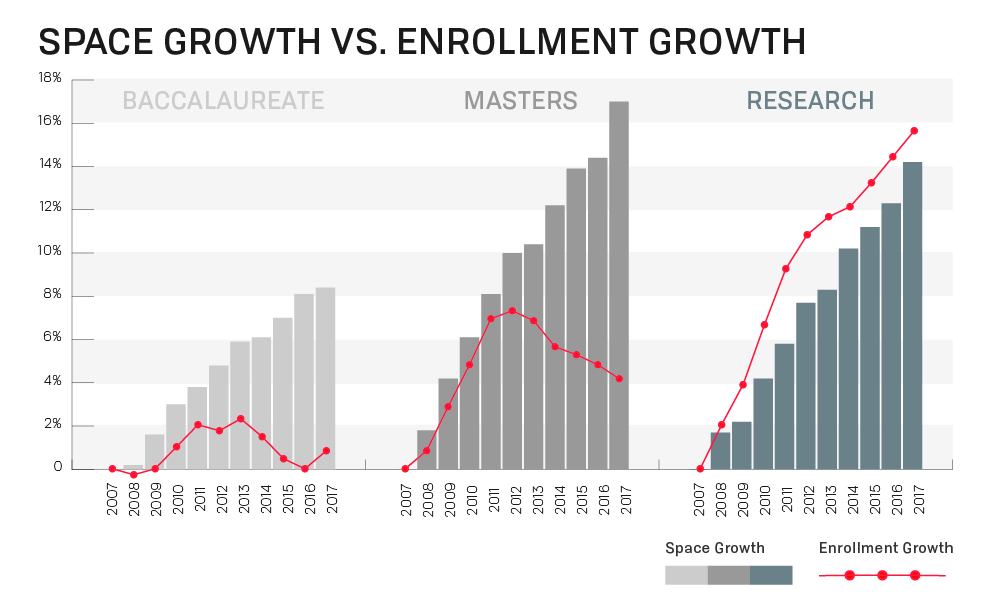

Being purely additive is not always feasible or fiscally responsible. In fact, the amount of space on college campuses has multiplied over the past ten years, despite declining enrollment numbers in baccalaureate and master’s programs. Existing facilities are aging to the thresholds requiring renewal of both space and systems, which has frequently been deferred in favor of new construction.

Institutions must balance funds for additional space, the forecast budgets of maintaining expanding facilities, and infrastructure with the pressures to minimize tuition increases. Space is a limited resource that must be programmed strategically.

Programming

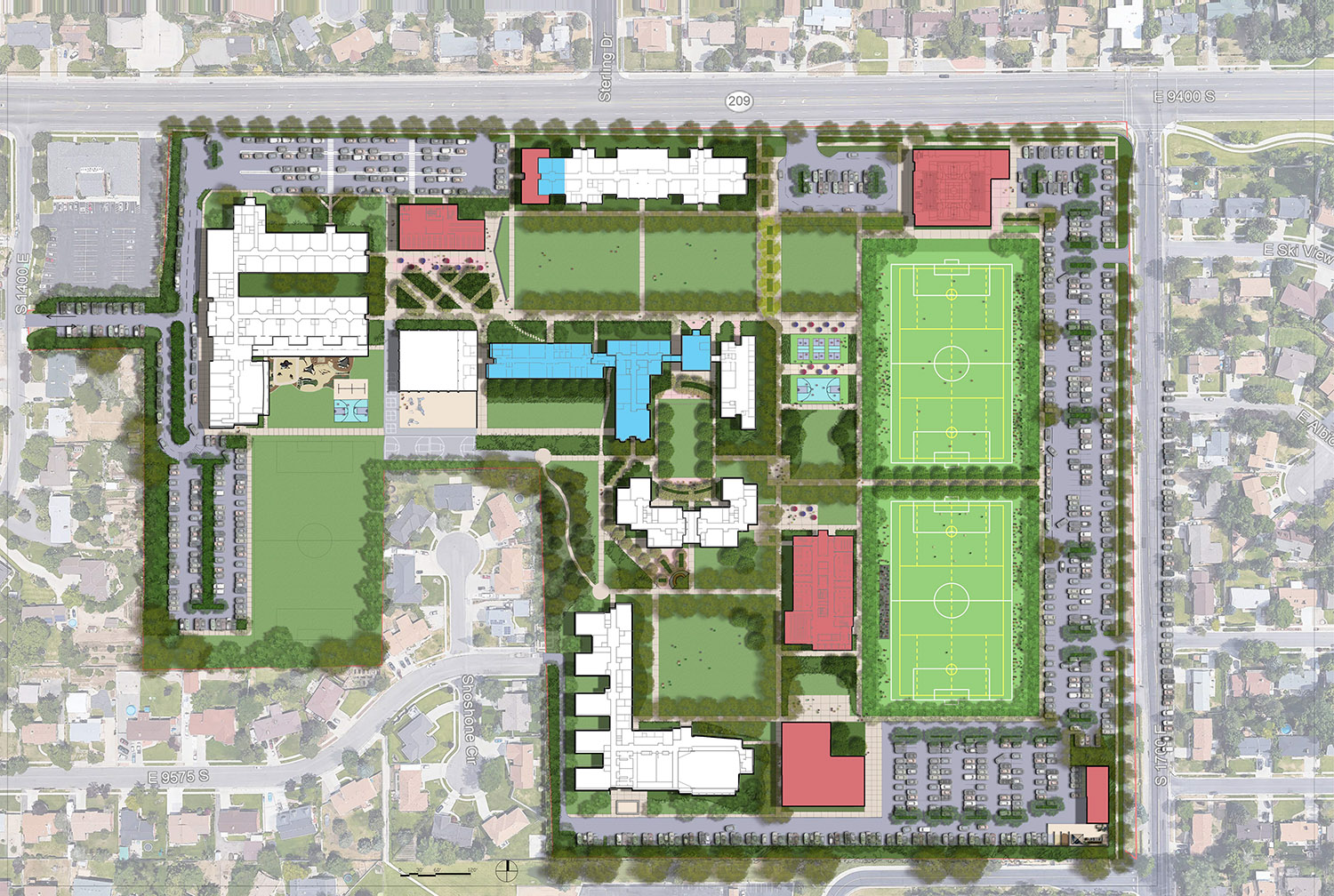

Strategic programming requires more than the measurement of classroom utilization. Likewise, it is ineffective to apply current trends assuming one solution can meet all needs. Programming is most potent when it fully understands the institution’s vision and translates the role of space to deliver on that promise.

Best practice would compare new needs to space that already exists as a critical first step, which identifies potential opportunities for efficiencies by re-purposing existing space. Then the full community would be engaged in the process; administration, faculty, and students, perhaps even alumni. Quantitative, as well as qualitative ethnographic methods, are applied. Then this matrix of information is analyzed to understand the variety of functions to be supported, allocated, and designed; tailored to the unique needs of the institution.

References

1 Bauer-Wolf, Jeremy. “‘All by Myself.’” Inside Higher Ed, 26 Oct. 2017, www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/10/26/isolation-loneliness-college-students-persists-partisan-era-college-campuses.

2 Terry, Esther, et al. “Changing Students, Faculty, and Institutions in the Twenty-First Century.” Association of American Colleges & Universities, 29 Dec. 2014, www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/changing-students-faculty-and-institutions-twenty-first-century.

3 Mark, Valenti. “Beyond Active Learning: Transformation of the Learning Space.” EDUCAUSE Review, 22 June 2015, er.educause.edu/articles/2015/6/beyondactive-learning-transformation-of-the-learning-space.

4 Selingo, Jeffrey J. “The Myth of the Well-Rounded Student? It’s Better to Be ‘T-Shaped’.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 01 June 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2016/06/01/the-myth-of-the-well-rounded-student-its-better-to-be-t-shaped/noredirect=on&utm_term=.4d354b16e550.

5 2018 State of Facilities in Higher Education, 6th Annual Report. Sightlines, a Gordian Company, www.sightlines.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2018-State-of-Facilities-in-Higher-Education_FINAL.pdf.

Article written by

Mary Sorensen

Design Strategist